A Non-Skateboarder's Skateboarding Guide to NYC

A self-guided tour of 8 notable skateboarding sites in Manhattan, New York City

So let me start by being fully authentic: I do not skate.

I tried. Halfheartedly in my teens, earnestly in my twenties, and in bits and spurts in my thirties—though never consistently or with much success. I still can’t ollie. My one and only skateboard is currently stuffed in the back of a closet, not touched in years.

So why would I write an article long enough that newsletter recipients interested in reading it in full—may the lord have mercy on your soul—will need to view this as a webpage?

Well, I may not skate, but I do like reading about it.

Truly. My bookshelf has a corner that’s over the years become dedicated to books by skateboarders and about skateboarding, and I’ve read quite a few by now. (My top recommendation is Rodney Mullen’s 2005 co-written autobiography, The Mutt: How to Skateboard and Not Kill Yourself.) Even though I suck at actually skateboarding, the culture, art, dance, music, and sport of it fascinate me. It’s about time my skateboarding library got some use outside my apartment!

Therefore, this is not a list of places to skate. I am not the right person to suggest that; NYC Parks has a comprehensive list of skateparks, and plenty of more appropriate content sources, like Red Bull, can point you to good spots to skate around the city. Rather, this is a list of places that trace the history and culture of skateboarding in New York City—specifically Manhattan—that are of historical or cultural interest to the hobby. Hopefully, this background also helps to explain why this article is riddled with citations. I am writing from a place of curiosity and research, not experience.

Taking the Tour

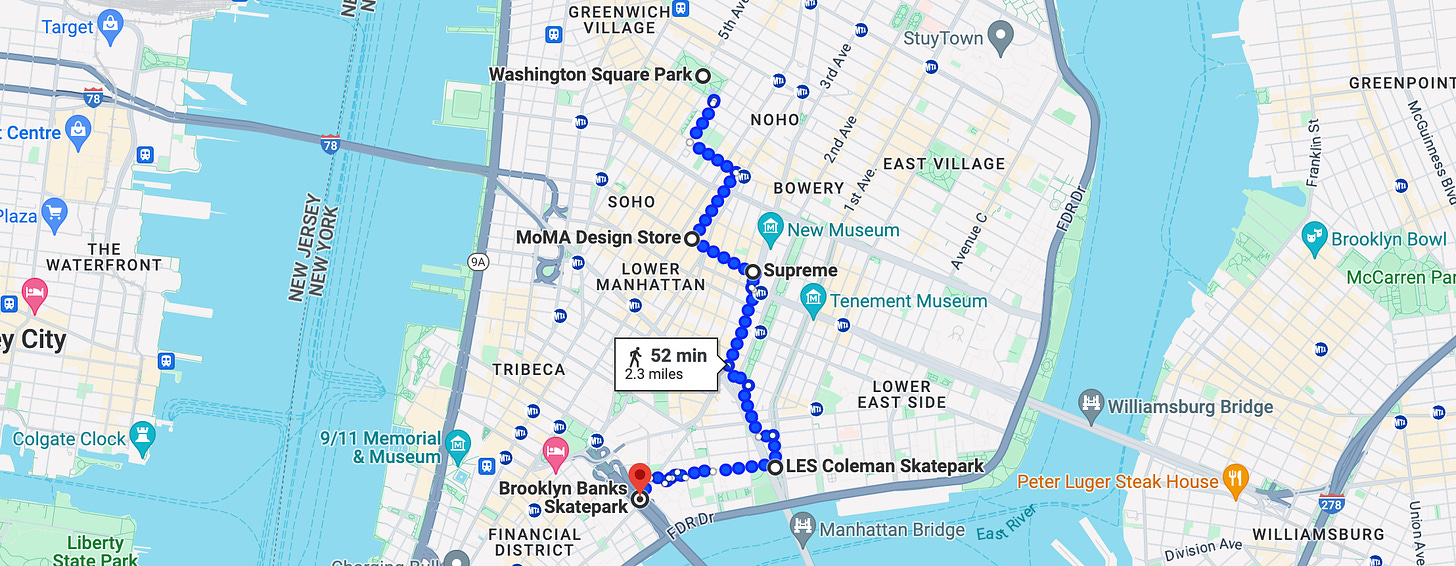

This article has been several months in the making and was written to be read top to bottom. While it is not necessary, if you really want this to be a self-guided tour and are able to commit to several miles worth of walking, you could visit many of these sites over the course of a day. The full location list for a self-guided tour looks like this:

The American Museum of Natural History (optional)

The Alice in Wonderland Statue (optional)

City Skateboards (not recommended)

Washington Square Park

MoMA Design Store

Supreme

LES Coleman Skatepark

Brooklyn Banks

I don’t recommend visiting the first three sites just for the purposes of this tour. Visit Site 1: The American Museum of Natural History only if you actually plan on spending several hours there. Visit Site 2: The Alice in Wonderland Statue only if you are looking to walk through (and potentially get hopelessly lost in) Central Park. Site 3: City Skateboards literally doesn’t exist anymore, but I do describe where it used to be. It is not a touristy area.

Site 4: Washington Square Park, along with Sites 5–8 can all be walked between and will require around an hour of walking (2.3 miles, or 3.7 kilometers) through Lower Manhattan. This is a lively part of the city, full of shops, restaurants, and attractions. You can get anything from low-end weed to high-end watches. If you go on this walk, let yourself be distracted!

For a slightly shorter tour, I recommend skipping Brooklyn Banks. It’s an important site and a historical part of skateboarding in New York City, but as of this writing it is under construction and inaccessible. The best you can do is explore the surrounding area and peek through the construction.

With that out of the way, let’s get rolling. . . .

Introduction: Skateboarding in New York City

“Skateboarders consider New York one of the world’s best cities for their sport,” writes New York Times editor Justin Porter (2005). This is despite the fact that skateboarding is historically and culturally more of a west coast sport. New York City, however, has a lot going for it, like huge buildings with long ledges and parks with flat concrete and obstacles.

By now, every borough has skateboarders. RAD Boardsport has a video series that explores skateparks all around the city. However, both the historical origins and sociocultural center of NYC skateboarding are specifically in Manhattan. “Manhattan is skateboarders’ favorite borough because of the diverse physical environments that it offers,” explains researcher Chihsin Chiu (2009). The island’s congested roads bring cars to a crawl but make for a complex, ever-changing landscape for skaters to cruise along. Chiu continues:

Midtown has a number of corporate plazas and courtyards often adorned with marble benches, staircases, and sculptures, which serve as great obstacles for skateboarding. Downtown offers the Brooklyn Banks, Astor Place, Union Square Park, and Battery Park City. In between, skateboarders enjoy traveling along the streets, between vehicles, and along sidewalks.

Ironically, despite the car-filled streets of Manhattan being a place to find skaters, part of what distinguishes skateboarding in New York City is that getting around isn’t car dependent—something unheard of in most of the west coast. New York City has “so many spots and you don’t have to go in a car; you can just cruise around the streets and see what’s happening” (Nieratko, 2010). Within the United States, NYC is uniquely dense with places to see and skate.

New York has over the years become friendly to novice skaters, too. It has “40 Parks Department-sanctioned skate parks, miles and miles of poured concrete and obstacles designed specifically for skateboarding” (Louison, 2023a). However, it is not the city’s official parks that make it a city of skate legend. “In New York, street stylists refuse to be confined to designated skate parks or vert-o-ramas,” writes author Jacob Hoye (2003). “They want to grind benches, wallride facades, tailslide monument bases. In short, they want to cover the same terrain as pedestrians, and then some.” Veteran skaters seek out “spots,” or city elements not designed for skateboarding that present an impromptu opportunity for a skateboarder to use a space creatively.

Part of the appeal of NYC is how hard the perfect skate spot can be to find and how quickly it can disappear. Even though the city has good skate spots, “the act of creatively interpreting urban space is constant and an entirely new way of seeing the world” (Snyder, 2017, p. 31). Between constant construction and changes to land rights and regulation, skaters in the city must adapt. “The conditions of what allows a spot or skatepark to emerge, then stay or are banned or dismantled, can change,” explain researchers Indigo Willing and Anthony Pappalardo (2023). “And it is why skaters in New York or other major cities are also creative thinkers because random street spots can change every day.”

Site 1: The American Museum of Natural History

I begin this tour here in part because, practically speaking, it provides an easy way to pair this tour with a museum visit. The American Museum of Natural History, or AMNH, is enormous, time-consuming, and does not have any skateboarding-specific objects in its collection. (Contrast this with Washington, DC’s National Museum of American History, which has a vast collection that includes Tony Hawk’s first skateboard.)

The history of skateboarding is not one thing, and the art, architecture, geography, and culture of skateboarding are all explored to different extents in this article. An early lesson for photographer Diane Arbus was that “the more specific you are . . . the more general it’ll be” (Palumbo, 2018). Examining the architecture that is best suited for skateboarding is examining architecture in general. Examining the social dynamics of skateboarders is examining sociology in general. Even the evolution of modern skateboard design can be reasonably modeled after biological evolution—a theory that was in fact co-developed by AMNH paleontologist emeritus Dr. Niles Elridge (Prentiss et al., 2011). The activity of skateboarding can be an “interdisciplinary lens for exploring” practically any human pursuit (Smithsonian Institution, 2016).

The full history of a recreational board goes back centuries and “owes its heritage to the papa he’e malu (surfboards) and papahōlua (land sleds) of Native Hawaiians” (Smithsonian, 2017). In the late 1800s, three princes from Hawaii attended college in San Mateo, California and in effect brought surfing with them. Writer Lizabeth Craig (2014, p. 8) tells the story: “They rode the waves on boards made from the local redwood trees. The sport quickly caught on, and by the late 1940s, surfing had become an extremely popular sport in California.”

Waves are unpredictable, however. They can only be surfed when they’re sufficiently high and close to the surface. Attaching wheels to surfboards added physical risk, but it gave surfers “some kind of similar activity they could [do] to maintain and improve their skills at times when the waves were low and surfing was not possible” (Craig, 2014, p. 9). It’s hard to pin down just when wheels attached precariously to surfboards started to look more like a skateboard as we know it today. “There is no real record of the first skateboard,” according to skateboarding writer Mackenzie Eisenhour (2023, p. 10). “As far back as the ’30s and ’40s, there are scattered records of people riding various wheeled contraptions.” However, by around 1950, surfers rolling down sidewalks had emerged as a popular activity in California.

Santa Monica surfer Larry Stevenson began selling skateboards in 1963 “through sporting goods and department stores in California, New York, Miami, and St. Louis and promoting them through his magazine, Surf Guide” (Turner, 2019, pp. 104–105). Over 50 million skateboards were sold within three years, becoming a national phenomenon. “Sidewalk surfing is catching on. . . . It’s even going over big right in the heart of New York City” (Smith, 1965, p. 41). By the early 1970s, thanks to developments into the engineering of a skateboard, the activity became safer, more versatile, and practiced by youth around the country (Francis, 2023, p. 7):

[The] ’70s saw sidewalk surfing’s second wave as a result of major developments in the device’s core components. The production of polyurethane, the material that’s used to make wheels to this day, led to smoother and quieter rides, and specially designed trucks were fabricated with axles that allowed for steady turns.

After the polyurethane “second wave” of the 1970s, skateboarding infiltrated the merciless parks and streets of NYC in its own way, and the rebel-punk ethos of skateboarding started to form. “Its first adherents were a loose-knit community of skateboarders and graffiti artists known as the Soul Artists of Zoo York” (Martin, 2009). One of the graffiti artists, Marc “Ali” Edmonds, was the one who coined the name: “New York is not new,” Ali said. “It’s a zoo” (Carayol, 2009).

The skateboarding community’s most frequented hangouts, at least at first, were along Upper Manhattan, putting AMNH in a prime location. The exterior of AMNH is filled with ledges and benches, making it “one of the best skate spots in New York City” (Panza, 2022). “There’s so many possible [tricks] to do.” The large Central Park-facing entrance, along with a few other parts of the surrounding architecture, are ripe for being “reconceived” by skaters (Borden, 1998, p. 254):

New York’s Museum of Natural History [is made of] 100 yards of Italian marble, marble benches curbed for frontside and backside rails, six steps, and statues of famous dudes with marble bases . . . basically an awesome skate arena.

The above video is from a trove of early 2000s footage that was recently found and posted online (Jenkem Staff, 2022). Skateboarder Billy Rohan gives a “masterclass” along the benches surrounding one of the museum’s entrances.

Site 2: The Alice in Wonderland Statue

Through the 1970s, New York was thousands of miles away from the flourishing California skater scene and hardly had any skateparks. As a result, for many years the skateboarding scene was a wild, wild west with unforgiving streets and uncharted architecture. Law enforcement and security guards in NYC were also more lax than in the west coast. “This city is always so hectic that security guards and cops don’t really care that much about wooden toys with rubber wheels,” theorizes skateboarder John Hill (2019). In a 1981 letter to Thrasher, “Charles” complains how the city’s skaters aren’t even in the burgeoning magazine: “I still can’t believe you haven’t covered the skaters of New York City. We have some of the most radical terrain in the nation” (Riggins, 1981, p. 7).

Skateboarders frequented many parts of Upper Manhattan, but the “Alice in Wonderland statue in Central Park was the center of the action,” according to skateboarder and artist J. J. Veronis (2021). It is a place where skaters who were a part of the early scene gathered, practiced, and marked territory. The bronze sculpture is also a shining example of modern urban architecture (Cushing & Pennings, 2017):

[The] setting of the ‘Alice in Wonderland’ sculpture includes a pedestal with low risers that invite and encourage people to move up towards the sculpture. These features act as a welcoming entrance to the space, with an accessible ramp, as well as walls and benches that afford opportunities to sit and directly view the sculpture. Visitors can circumambulate the sculpture, observing it in detail from all sides. . . . [The] sculpture affords climbing and sitting through the inclusion of small mushrooms that represent steps up to Alice. The design of the sculpture also provides small, intimate spaces underneath the large mushrooms where children can hide. . . .

For as long as there has been a skateboarding subculture, struggle and risk-taking have been “key markers of dominant skateboarder authenticity” (Abulhawa, 2020, p. 68). The Alice in Wonderland sculpture was a spot where skaters gathered, establishing an in-crowd and “terrorizing wannabes” (Witten, 2016). Skateboarder and writer Cole Louison (2023b) explains how the territory spread out from there into the surrounding Upper Manhattan: “Skaters would gather, then disperse throughout the park and beyond, bombing hills by Tavern on the Green or at 9th Ave and 78th street, or—before security appeared—ride the brick transitions at Lex and 53rd or 89th and Madison (which remain today).”

By the 1990s, “New York was no longer an addendum to Californian skateboarding, but firmly established as a premier world skate city” (Borden, 2019a, p. 83). Skaters dispersed throughout the city, and new hubs would soon be formed in Lower Manhattan, a history that is described in more detail starting with Site 4: Washington Square Park.

Site 3: City Skateboards

In New York City’s earliest skateboarding days, there weren’t many places to buy a skateboard. Your best bet was to check large sporting goods or department stores or buy them through a mail order catalog, likely from a shop based in California. New York City’s commercial history with skateboarding arguably begins with City Skateboards, at 221 East 83rd Street. (Note: most sources say 83rd Street, but a 1978 New York Times article wrote 81st Street, and I haven’t been able to confirm.) Wherever it was, it’s no longer a skateboarding store and barely distinguishable from the adjacent prewar buildings.

Skateboarding is one of many activities where the city’s culture is dominated by its most skilled practitioners (Nieratko, 2010). Yet, the playing field is not equal when it comes to being accepted within the social community and afforded a chance to develop skill in the first place. In discussing the story of skateboarding, I feel that there is a white elephant I have so far been ignoring—if you’ll excuse the expression. While a healthy, able-bodied person can learn to skateboard from a kinesthetic perspective (though being able-bodied is not a strict requirement), those who skate do tend to fit certain sociocultural characteristics. In my examination of the history of skateboarding in New York City, I came across unquestionable evidence of misogyny, racism, homophobia, and transphobia.

Willing and Pappalardo (2023) elaborate: “Until fairly recently, many skateparks had a certain locker-room feel, with gay slurs and insensitive jokes. There is even a 1980s-era trick called the ‘gay twist,’ a homophobic reference to it being ‘the gay way’ of performing a particular kind of aerial.” As recently as 2013, a prominent skateboarder made news after saying in an interview that “girls shouldn’t skate at all” (Abulhawa, 2020, p. 104), and there is no question that girls and young women must “work harder than male peers to be taken seriously as athletes” (Coakley, 2015, p. 284).

Professional—and transgender—skateboarder Leo Baker (2021, pp. 6–7) recounts the difficulty of being accepted into the skateboarding community: “I experience transphobic microaggressions on a daily basis. . . . For years I was pushed aside because the industry didn’t know what to do with me. They didn’t know how to accept a tomboy skater.” It benefited skaters to be white, as well. “While skateboarding’s earliest history as a homemade toy can be located in urban neighborhoods, its commercial and more mainstream history is . . . denied to African Americans” (Yochim, 2010, p. 32). The popular images of skateboarding and the communities in which it flourished were overwhelmingly white.

This is the context in which City Skateboards opened. Now there are dozens of skate shops across all boroughs, but access to skateboards was at first easiest if you lived in the fashionable—and expensive—Upper East Side. At the end of the 1970s, this area of NYC was among the “most desirable” in the city: “developed . . . to serve the needs and tastes of New York’s upper classes, the [Upper East Side] continues to attract those who appreciate its choice location adjoining Central Park and its handsome town houses and luxurious apartment buildings” (City of New York, 1981, p. 13). A brief article in a 1978 issue of New York Magazine paints a picture of the “navy-blazered” kids who shopped there (Stern, 1978):

“It used to be a fad. Now it’s a sport,” says Joe Brennand, blond and thirteen. He’s one of the after-school crowd at City Skateboards, hanging out, gazing at the goods. These are preppie kids, bright-eyed, navy-blazered, and zealous. . . .” (p. 83)

For aspiring skateboarders in the 1970s and 80s, purchasing basic equipment wasn’t cheap. A fully-assembled skateboard would commonly run around $50, or around $172 today. There are plenty of hidden costs too, such as safety equipment and replacement shoes and skate parts that inevitably get destroyed. In the extreme, when City Skateboards first opened, the store even sold a $325 “Motoboard,” or motorized skateboard—around $1,500 today. (New York Times, 1978).

Nowadays, in light of a more globally connected world and recent reckonings with systematic injustices against women, people of color, and members of the LGBTQ+ community, skateboarding “attracts people from all walks of life” (Atencio et al., 2018, p. 12). Youth in and around New York City have safe parks to skate in, and skaters of every age have discovered architecture in the city that may not have been designed for skateboarding but is perfect for it. Plus, the days of City Skateboards being the only place to buy a skateboard are long gone. A functional starter skateboard can currently be found at places like Walmart for $10 or less.

Site 4: Washington Square Park

As a nationwide fad, skateboarding had a peak in the 1980s. It was still predominantly a west coast activity, but more stores popped up around New York City, including grungier, more culturally authentic “OG real” skate shops near Washington Square Park (Carayol, 2009). California was sunny skies, ample space, and carefree skating. New York was dirty streets and chaos. Famed skateboarder Rodney Mullen reflects on his time being flown into the city for paid public demos in the mid-1980s (Mullen & Mortimer, 2004):

After two days in New York, my head was spinning. All the performers had to take a bus out to a required dinner, and I’d hear nonstop chatter about their gnarly activities from the night before. I was surrounded by models who snorted coke off fashion magazines and talked like bisexual sailors about their sleazy escapades and who on the bus was a better screw. (p. 150)

NYC skateboarders did not yet have empty pools and city-sanctioned skateparks that made it a youth-friendly sport. “Skateboarding here is born from New York’s de-industrialization and middle-class white flight, where crime-infused, drug-ridden and graffiti-coated city territories encouraged graffiti artists, skateboarders and other space-appropriating creatives,” writes architectural historian Iain Borden (2019a). Washington Square Park specifically became a “democracy of derelicts, drug-dealers and buyers, street performers, buskers and skaters.”

In the years that followed, skateboarding fell out of favor, and extant skaters formed an exclusive crew that would change the face of the sport. “Modern skate culture is incubated during these early ’90s years,” writes Mackenzie Eisenhour (2023). “By the time it is depicted in Larry Clark’s Kids in ’95, skateboarding exists as an entirely different pastime than during the three decades prior.”

Now let’s talk Kids. The film is difficult—if not downright unpleasant or problematic. But it has also emerged as a critical text. Consider the reflection of author bell hooks (2005, p. 16): “Kids fascinated me as a film precisely because when you heard about it, it seemed like the perfect embodiment of [postmodern] journeying and dislocation and fragmentation and yet when you go to see it, it has simply such a conservative take on gender, on race, on the politics of HIV.”

The film, a “gritty look at a group of skateboarding, drug-abusing, bed-hopping teenagers, became an unlikely a box office hit when it premiered in the summer of 1995” (Lang, 2021). The controversial film was directed by Larry Clark, produced on a shoestring budget, and starred then-unknown teenagers Chloë Sevigny and Rosario Dawson, along with iconic skater Harold Hunter, who passed away of a narcotic induced heart attack in 2006. Sociologist Duncan McDuie-Ra (2021) reflects on Hunter’s life both in and out of the film: “Hunter, who was a professional skater at the time and a stalwart of [NYC] skateboarding when it was still in the cultural margins . . . seemed to affirm the story line in Kids; a grimy underworld of dangerous youth deliquency spurred by an uncaring society and a prognosis for an unending cycle” (p. 86).

The film gained such notoriety that it’s hard to say whether it was dramatizing or influencing skateboarding culture, but regardless, it paints a sobering picture of NYC skateboarding in the 1990s. “The film focuses on the New York City skater lifestyle—as it was in ’95—steeped in alcohol, drugs, petty crime, and ultimately the AIDS epidemic” (Eisenhour, 2023, p. 176). Kids is unsparing with blatant portrayals of sexual violence and homophobia. “Washington Square Park was the ’90s epicenter, and it’s no accident that a dark cult film synonymous with gritty NYC street culture was shot here.”

It was at the park where skateboarder Harmony Korine, who wrote Kids, met director Larry Clark. It was also at the park where “some of the film’s most jarring sequences take place amid the backdrop of the park’s iconic fountain and arch” (Connor, 2015). During this time, Washington Square Park established itself as the first “spot” for skaters to congregate, alongside the now-famed Brooklyn Banks (Site 8). Skateboarder Steve Rodriguez describes the earliest days of skating Washington Square Park (Lee, 2011): “Since they redid the park it’s just one level but it used to be two levels. A lower level, an upper level and in between the two were these banks that were pretty steep, along with ledges.” Word of mouth traveled quickly, and the park attracted skaters from all around the New York metropolitan area (Campo, 2013, p. 36).

Washington Square Park remained central to NYC skateboarding until 9/11. The attacks that day had an effect within many subcultures, skateboarding being no exception. Lower Manhattan has long been a prized part of the country to skate, and “dozens of skate spots [were] lost to terrorism” (Hamm, 2004, p. 180). It wasn’t just that spots were destroyed; many became inaccessible or unskateable. The Brooklyn Banks, for example, was “deemed a potentially sensitive area that might be of value to terrorists intent on destroying the iconic bridge above” and was temporarily closed to the public (Campo, 2013, p. 36). Additionally, security increased, and skaters found themselves less welcome in the city’s parks, especially at night (Louison, 2023b).

Site 5: Museum of Modern Art Design Store

I use many terms to refer to the act of skateboarding: sport, hobby, recreation, and so on. Skateboarding isn’t just one thing. It was introduced into the Summer Olympic Games in 2020, where contestants surely prepared for it as a sport. But even then, it falls into a similar class as gymnastics or ice skating, where the sport has an artistic component to it. Part of a skater’s prowess includes not just the technical difficulty of the tricks, but the way the skater looks while skating. Around ten years ago, the phrase “I’d rather watch Gino push” became popular within the skateboarding community, referring to Gino Iannucci’s inimitable style while simply rolling around on a skateboard. “You could just watch him cruise all day,” reflects UK skateboarder Carl Shipman (Macdonald, 2020). “He had that style about him where he could just push and it looks good.”

The artistic side of skateboarding includes a literal component too: the main, wooden Popsicle stick-shaped part of the skateboard, i.e., the deck. While the top is covered with griptape, the underside of skateboarding decks “had been adorned since the 1970s as a way to mark brand identity and skater individuality” (Lepercq, 2021). Just as with clothes or cars, the brand itself can be a part of the consumer’s identity. It may represent who is sponsoring the skater—either with money or with other perks like merchandise—or what the skater considers cool. The deck can also telegraph certain values, like when using a deck by Proper Gnar, a brand started by Black women. The images on the deck can display anything from fine art to pornography, with brands typically having a point of view regarding what to feature.

Skateboarding itself, a recreation filled with daring and individuality, can serve as inspiration for artists, though it is not easy for an artist to break into the world of skateboarding. Being “authentic” is deeply prized among skateboarders, a quality found in adjacent subcultures like those of graffiti, hip hop, and punk. “[When] you talk about skateboarding and art—there are so many bad connotations within that,” explains artist Ryan McGinley (Spiotta, 2008, p. 49). “There are a lot of artists that made ‘skateboard art,’ which is bad, like really bad.” In other words, artists can’t get the cultural cachet that comes from being a skilled skateboarder simply by making art on or about skateboards. McGinley, now a photographer, grew up traveling to NYC for skate sessions (p. 48): “I’ve been going to museums my whole life [like] to the Museum of Modern Art on school trips [but when] you go and look in a museum, it’s as though it’s not real. Most of the artists are dead and it’s already part of history.”

While one is unlikely to find skateboarding-related art among what’s currently on display at the Museum of Modern Art, or MoMA, the same is not true for their gift shop. In fact, MoMA has multiple gift shops, including a design store in SoHo, several miles downtown from the museum. There, at least as of this writing, skateboards designed in partnership with notable modern artists are on display and can be purchased.

This relationship between skateboarding and fine art has existed for decades. Skateboards provide the perfect canvas that is not only tied to self-expression but exemplifies both form and function. As early as 1983, famed artist Keith Haring wanted to “make more functional items” like skateboards, which were sold at the Pop Shop, a store he founded to ostensibly bring fine art to the masses (Raffel, 2017, p. 136). Artist Brian Donnelly, better known as Kaws, reflects on Haring’s shop:

When I was a kid my first introduction to art came through graffiti, skateboarding, and the Pop Shop. . . . I remember the way Keith Haring’s art made me feel comfortable walking into a gallery or museum. (p. 277)

Eli Morgan Gesner, one of the founders of NYC-founded skateboarding brand Zoo York reflects on a happenstance meeting with Haring (Friends from New York, 2023):

One night, [I was watching] a report on a young Keith Haring. . . . . Literally the next day, my skateboard pal wore his first run, hand made, Keith Haring ‘Radiant Baby’ tee his Mom bought him earlier that year. Just a crappy white tee with a one color black graphic. We headed down to SoHo on our skateboards when we hear - “Hey! Skaters!” - we look and it’s fucking Keith Haring running across the street to us. “No way! I made that tee shirt!” he told us. “No way! We just watched you on TV last night!”

Despite Haring’s influence on skateboarders in the 1980s, there is still a sense of an outsider looking in. Keith Haring was a phenomenal artist, but he was not a skateboarder. His skateboards were to be used, not hung on a wall. Enter Ryan McGinness, who grew up amid a culture of skateboarding and graffiti in Virginia Beach, Virginia during the 1970s and 1980s. He experimented with painting directly onto a skateboard. His early influences are evident in his drawings, paintings, and sculptures today. “Although painting on wood panels has been a tradition in art for centuries, the pill-shaped oval of the skateboard deck afforded a new format, and McGinness was attracted to the medium for its fresh formal qualities and its value as a symbol of youth culture” (Gladman, 2002). The MoMA (2016) currently has a few dozen of his works in its collection.

In 2000, McGinness collaborated with Supreme (Site 6) to launch an “Artists Series,” marking not only a rare instance of a deck being designed from someone coming from the fine art world, not the skateboarding world, but the first time that Supreme ever collaborated with an artist. Writer Edmée Lepercq (2021) describes the series:

Titled Supreme Color Formula Guide, it made full use of the deck’s unique oblong shape, creating a supersized Pantone color scheme with whiffs of Pop Art and Minimalism. The edition marked a departure from the dominant trends in skateboard deck art at the time, which were cartoonish if not outright pornographic or satanic.

A commonality between art and skateboarding is that both of them are able to effect change. Art can be a source of enormous fundraising for good, and art itself can shock, awe, and confront. And skateboarding can provide social, health, and economic development in places where people, especially youth, struggle to find it (Abulhawa, 2020, p. 81). One notable organization, Skateistan, was founded in 2007 in Afghanistan where community around sports—especially for girls—was difficult to find. The country was under Taliban rule, where “everyone was desperate for something fun to do, but even sports were banned. . . . Anyone found playing football or other sports on the street was beaten or arrested, whether they were seven-years-old or 70” (Fitzpatrick & Skateistan, 2012, p. 13). The nonprofit has since expanded to provide skateboarding community and education to youth around the world.

In 2014, Belgian art dealer Charles-Antoine Bodson “was so impressed by the work of Skateistan that he decided to sell part of his skateboard collection” and work with “iconic artists” to create skateboard art and raise funds (Habjanovic, 2017). He founded The Skateroom, a nonprofit devoted to effecting social change. The skateboards sold for the nonprofit are meant to be displayed on a wall: “Some artists are starting to play with the material of the skate deck itself, pushing its functionality to the limit. . . . . Walead Beshty used copper for his deck, while Jenny Holzer, created a marble skateboard” (Lepercq, 2021). The MoMA Design Store is the exclusive vendor for many of these limited-edition skateboards, with a portion of all proceeds dedicated to social change (Smith, et al., 2016).

Whether this is commodifying the sport or elevating it is up to you. But the Museum of Modern Art has leaned into the creativity and expression of skateboarding, partnering with artists, artist estates, and non-profits to produce skateboarding decks with art by world-famous artists such as Yoshitomo Nara, Yayoi Kusama, Andy Warhol, Jean-Michel Basquiat, and Ai Weiwei. Like most great art, it’s more than for pleasure, it’s for a cause.

Site 6: Supreme

Historically, as I describe throughout this article, skateboarding is more of a west coast than east coast activity. The history of brick-and-mortar skate shops likely begins with Val Surf, which opened in 1962 in North Hollywood. For many years, the commercial side of skateboarding in NYC was limited. The city didn’t have its own skate shop until 1978, as described in Site 3: City Skateboards.

Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, “skateboarding survived as a self contained underground youth subculture, largely outside the mainstream of popular sport” (Turner, 2019, p. 131). The activity was most often found on the streets, where the most revered skaters were those who could perform the hardest tricks. Sociologist Gregory Snyder explains (Rathbone & Snyder, 2018):

There’s the history of bowl skating or skating in empty swimming pools, and then people skated on . . . vert ramps [like] Tony Hawk. . . . So in the late 80s, early 90s, there’s sort of this democratizing influence where skaters who didn’t have access to ramps began to skate on and . . . creatively reinterpret urban obstacles in which to perform tricks.

There was no avoiding that in order to learn tricks, one had to be willing to fail often and fall hard. Those who dominated this kind of subversive counterculture were often reckless and dangerous. “The city was super gnarly, really out of hand,” recalls famed skateboarder Steve Rodriguez (Lee, 2011). “I saw some guy, throw a can of soda at an old lady, hit her on the back and watched her hunch over in pain while the whole group was just laughing.”

New York City may not be the birthplace of skateboarding; however, it is the birthplace of another subversive counterculture: hip hop. Hip hop and skateboarding both “operate within the habituated common spaces of everyday life,” explains anthropologist Nicholas Wees (2022, p. 108). “They also suggest some other possibility, some other way of conceiving of, perceiving, and acting in the world—both for the individual practitioners and for the casual witness.”

Skateboarding may have come from the west coast, but a hip hop-influenced skateboarding fashion was evolving separately. The hip hop and rap connections especially “complete skateboarding’s divorce from its surfing-centric beach roots,” making skateboarding “nearly ubiquitously associated with cities” (Eisenhour, 2023, p. 41). New York Times writer Jon Caramanica (2011) comments specifically on how skateboarders listening to hip hop gave way to a fashion that addresses some of the racial barriers seemingly endemic to the sport:

[People are wearing] the collision of hip-hop fashion, skateboarding gear and work wear that’s generally called street wear. It's a neat trick of deracination, or post-racination. As rap music seeps more and more into the fabric of pop culture, its accoutrements become more familiar. . . . The results are tough but relatable, a style that connotes insiderdom while excluding no one.

When the NYC-founded Supreme store opened in 1994, Coolio, Salt-N-Pepa, and Snoop Dogg all had hits on Billboard’s Top 40. Supreme marked a new era of skateboarding fashion. Skateboarder and writer Cole Louison elaborates (2023b): “Some say this was the beginning of streetwear (a $300 billion industry today) and it makes sense, considering that in 1994, a tiny shop . . . that sold decks, hardware, and t-shirts screened with one word: SUPREME.” The store fundamentally questioned what a skate shop was supposed to look like. Piles of clothes are replaced by representative samples, and instead of a graffiti aesthetic, the colors are bold, blocky, and vibrant—“more like an art installation than a display of commercial goods or products” (Hoye, 2003, p. 5). Ironically, while the inside may be clean and minimalistic, the outside of the current building is perpetually covered with graffiti.

Part of the store’s allure was that it had all of the unspoken barriers to entry as a high-end clothing store but none of the pesky courtesies like kindness or patience. The store was known for “extremely poor and crass customer service” (Rajendran, 2012). “The low level of tolerance for those unaware with in-store rules—no unfolding, stock is in the back, limited questions, and a get-in-and-get-out policy—has still allowed the brand to thrive.”

Supreme went from a skateboarding staple to global phenomenon roughly a decade ago (Eisenhour, 2003, p. 24): “Supreme releases the video Cherry by Bill Strobeck in ’14, launching the apparel brand into the stratosphere.” The subsequent hype of the video—with a soundtrack including hip hop artists Cypress Hill and Chief Keef—turned the Supreme store into a commercial mecca for skaters everywhere (Rajendran, 2012):

During the Fall/Winter release on September 7, 2011, 250 people between the ages of 12–45 braved an overnight rainstorm while waiting for new releases. One of the first in line, Nigel Powers from Toronto, took an 8-hour bus ride for this event.

Its popularity grew even more in 2016 when Dylan Rieder, one of the stars of Cherry, whose part is shown below, tragically died of cancer at only 28 years old. Part of Rieder’s legacy is the way he changed the aesthetic of skateboarding: from baggy clothes and graffiti to formal suits and classic Americana. “He was an iconoclast among iconoclasts, someone who refused to abide by any neat definition of what being a skater was supposed to look like” (Woolf, 2016).

Most skateboarding stories begin in California and then spread east. The story of Supreme is a rare example of a skateboarding story that began in New York and spread west. Its first west coast brick-and-mortar shop did not open until 2004, and it has since opened locations around the globe, including Paris, London, Berlin, and Tokyo. Supreme has in fact grown to be one of the “largest brands on the planet,” having been acquired for a whopping $2.1 billion in 2020 (Supreme, 2023; Eisenhour, 2023, p. 227).

Site 7: LES Coleman Skatepark

Often called the “LES Park” (for lower east side), “LES Coleman Park,” or some variant thereof, the Coleman Playground Skatepark is an example of not only a more modern history of skateboarding but also a microcosm of human geography, and how land can change names, boundaries, uses, and rights. Originally, of course, this park didn’t belong to the United States at all but to the Native American Lenape tribe. This part of Manhattan would have been near the bottom of their main trail, which people used to travel between encampments as seasons changed (Brazee, 2012). I direct those looking to learn more about the Lenape Tribe to the National Museum of the American Indian, which in 2010 actually had an exhibition on skateboard culture in Native America.

In 1804, a nearby church was founded that used this land as a graveyard (NYC Department of Parks & Recreation, 2015). Plaques located at the park continue the story from there. The church was sold in 1866, and two thousand bodies were exhumed and reburied elsewhere. Decades later, the park was acquired by condemnation and transformed into a playground. The “Coleman” name is in honor of US Army Corporal Joseph Francis Coleman, who died in 1919 after contracting tuberculosis in the trenches of World War I. The city had jurisdiction over the park at the time, occasionally expanding its area until it reached its present size in 1970.

The park was in disrepair for decades, eventually being reconstructed in 1974 but not often used. “The skatepark used to just be basketball courts, but I don’t even think there were hoops, it was just total sketchy,” explains skateboarder Steve Rodriguez (Lee, 2011). “Super shitty ground, the only thing you could do was ollie the stairs.” The city renovated it again in 2000, adding new play equipment, animal art, spray showers, and safety surfacing (NYC Department of Parks & Recreation, 2015). Around 2005, the city made its first attempt to turn it into a functioning skatepark, installing ramps and ledges. “They made the skatepark, and it was some prefab junk and fun for a while” (Lee, 2011).

The skatepark may have comprised “prefab junk,” but skaters did begin to congregate. It’s a phenomenon in some ways unique to skateboarding; skaters accept any space as an important destination so long it’s a spot conducive to skating. Gregory Snyder (2017) explains how this makes them, in a sense, “postmodern explorers”:

Skaters today . . . actively cross urban boundaries in search of spots and in doing so understand their city in an entirely different way. . . . In this sense skaters are postmodern explorers of the contemporary city unbound by country or continent or hemisphere. Skaters are citizens of city earth, constantly exploring, searching for new undiscovered places to expand their discipline’s notions of what’s possible, all the while developing an ever more intimate relationships with the urban geography of the world’s built environment. (p. 55)

It “wasn’t until a full redesign by [skateboarder] Steve Rodriguez” several years later that “LES became NYC’s new skate center” (Louison, 2023b). The park reopened in 2012 and has since been a staple in the NYC skateboarding world. The “good skate park design,” says Rodriguez, “is defined by the ability of skaters to flow through the park without stopping, each obstacle a logical, and playful, distance apart” (Ihaza, 2018).

It helps too that skate parks have become considerably “more welcoming of skaters of different ages, genders and backgrounds” (Borden, 2019b, p. 82). After all, New York City is not particularly hospitable to novice skateboarders, who are usually unable to practice in backyards and sprawling open spaces afforded to skaters in more rural or suburban areas. City-sanctioned skate parks are reliable places for burgeoning and advanced skaters alike, in effect being “vital sites for youth skateboarding” in New York City (Atencio et al., 2018). They ensure skaters aren’t spending time in spots that are perfect for skateboarding but unsafe and in disrepair (see Site 8: Brooklyn Banks). “It gets a lot of kids away from trouble. . . . If the park is closer, your instincts will be to go skate, versus whatever it is that could get you locked up” (Ihaza, 2018).

Coleman Skatepark was home to a large-scale art installation in 2017, where conceptual artist Barbara Kruger marked walls and obstacles around the park with bold text like “WANT IT. NEED IT. BUY IT.” and “THE GLOBE SHRINKS FOR THOSE WHO OWN IT.” The words used the “visual language of popular culture as a vessel for insight and criticism” (Chiaverina, 2017). The text was also white over a red background, a clear connection—though not quite an homage—to Supreme. It was Kruger’s art, in fact, which came first; Supreme was referencing her (Graphéine, 2022).

Site 8: Brooklyn Banks

The last site is a marvel of what happens when an urban landscape is accidentally perfect for an activity for which it was never intended. The Brooklyn Banks is the unofficial name for a specific skate spot under the Manhattan side of the Brooklyn Bridge. Its architecture and reputation have caused it to become famed well beyond New York City, with appearances across magazines, videos, and even the Playstation 1-era video game Tony Hawk’s Pro Skater 2. Urban studies expert Daniel Campo (2013) describes the area:

[The Brooklyn] Banks, which is actually in Manhattan, is an isolated plaza underneath and between two approaches to the Brooklyn Bridge. Where the plaza meets one of the approaches, it curves up into the supporting wall, forming an ideal if unintended skateable bank. The plaza is also inclined, which helps skaters gain momentum as they propel themselves onto the abutting wall and other “found” obstacles. The Banks is legendary and known to skateboarders all over the world. (p. 36)

For years it was a spot that no one visited and was slowly falling into disrepair. “It was a gritty and poorly maintained park rarely used by most people” (Chiu, 2009, p. 29). By the time skateboarding had its polyurethane revolution, there were plenty of skaters in New York City but no dedicated skateparks. The Brooklyn Banks addressed this problem, as it was coincidentally shaped ideally for a skateboarder. Not only was every curve and ledge skateable, but the skateable space was huge—able to accommodate hundreds of skaters at once. Space to spread out is already rare enough in NYC; skateable space to spread out was serendipity. “It was like the city’s gift,” says skateboarder Manny Pangilinan (Roll Skateboards, 2018).

Anyone who traveled to New York City with a skateboard was bound to stop by the Brooklyn Banks. “By 1985, the Banks was the absolute epicenter of New York City skateboarding” (Louison, 2023b). Pangilinan explains the appeal (Roll Skateboards, 2018): “You just followed wherever there was red bricks, and it was skateable. Everything was connected by banks. It was just bankland. . . . The banks connected to curves [that] were connected to ledges. . . . The banks were smaller but as then you got down they got bigger. Anyone from the east coast would go there to skate.”

The banks were perhaps canonized in the 1985 film Future Primitive by famed skateboarding director Stacy Peralta (Louison, 2023b). The video is shown below; at around 35:40, the skaters cross the Brooklyn Bridge into Manhattan and enter the Brooklyn Banks. Truthfully I cringe today watching the Bones Brigade’s rude disregard for strangers or safety, especially in some of the later scenes through midtown Manhattan, but there is no denying how the NYC part of the film “brought urban skating to a worldwide audience” (Carayol, 2009).

During the 1990s, skateboarding experienced a surge in popularity that lasted into the 2000s. (Avril Lavigne’s pop-punk classic “Sk8er Boi” was released in 2002.) There was an enormous gap between those who had been skating before it was trendy again and those who only recently joined the trend. Brooklyn Banks was the place most renowned for having a “locals-only home turf . . . or ‘survival-of-the-fittest’ mentality, where new arrivals met with hazing, theft and intimidation” (Borden, 2019a, pp. 29–30). Even as skate parks appeared and the activity gained popularity, there was never much of a city effort to make the park usable to anyone else. “For decades, nobody wanted the space except the skateboarders” (Porter, 2005).

In 2005 the park was revitalized under the guidance of veteran skateboarder Steve Rodriguez. The city removed some benches and planters to make more of the brick ramps accessible to skaters and generally made the space safer and greener (Porter, 2005). Its reopening was decades in the making and transformed the park into a “monument to NYC skateboarding—a 50-year-old microculture” (Louison, 2023b).

Unfortunately, the new era for the Brooklyn Banks was short lived. In 2010, the city took over the Banks in order to use the area for reconstructing the Brooklyn Bridge. “The plaza was supposed to close for four years, according to city officials at the time, but it never reopened,” writes New York Times journalist Winnie Hu (2023). “Restoration of the bridge is expected to stretch to 2024.” If you travel there now, you’ll find barricades and construction, but the story of the Brooklyn Banks is not over yet. Just this past year, Mayor Eric Adams has announced potentially refurbishing it as a part of a $160 million development (Louison, 2023a).

Conclusion: Skateboarding as Medicine

The story of skateboarding is one rich in history that is paradoxically both inclusive and exclusive. Learning to perform tricks on a skateboard is a challenging feat requiring dedication and bravery. Even just learning to balance on one can feel freeing and expressive. Those who succeed are rewarded with a perspective of the city shared by a select few and entry into a special community. “A few times, there was spontaneous applause,” observed writer Bill Hayes (2017, p. 135), while watching skaters at a New York City skatepark. “I’d never heard that before. These boys were not just skating for the fun of it, the thrill; they were competing for ‘who’s best.’”

Emphasis perhaps on “boys.” The skateboarding community of New York City mirrors the very city itself, which on the whole is safe and welcoming, but when inspected up close, has the trappings of bigotry, class divisions, and unkindness that can mark the darker side of the human condition anywhere. The hobby of skateboarding is most easily accessed by those who look and act a certain way and can afford to keep replacing sneakers and skate decks. Yet what better way to say “eat the rich” than to nosegrind along a marble ledge on Wall Street?

In the course of creating this post, I’ve found myself looking at the city a little bit differently. When I see people carrying or riding skateboards, I have to resist an urge to ask them where they skate and why they skate. When I see architecture that looks skateable, I look for scratches and wax marks to confirm my suspicion.

Given the primary purpose of my Substack—to curate a monthly list of events happening around NYC—I searched hard for anything skateboarding related to include in an upcoming list, but alas, while this city may have everything, it doesn’t literally have an event for every form of expression all the time. I guess my curatorial work still has a purpose. That said, artistic and cultural events pertaining to skateboarding do pop up from time to time. There have been skateboarding-themed exhibitions at the Museum of Modern Art, the National Museum of the American Indian, and Industry City, to name a few examples, along with occasional film screenings of skateboarding videos or movies about skateboarding. It’s a safe bet that when anything like this crosses my radar, it will make a future list.

I’ll finish with a quote by art historian and writer RoseLee Goldberg, commenting on Barbara Kruger’s art installation described in Site 7: LES Coleman Skatepark (Chiaverina, 2017): “Just watching these people go back and forth and back and forth, it’s totally meditative and gorgeous. A spoonful of sugar makes the medicine go down.”

Works Cited

Abulhawa, D. (2020). Skateboarding and Femininity. Routledge.

Atencio, M., Beal, B., Wright, E. M., & McClain, Z. (2018). Moving Boarders: Skateboarding and the Changing Landscape of Urban Youth Sports. The University of Arkansas Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv7vcss3

Baker, L. (2021). Skate for Your Life. Penguin Workshop.

Borden, I. (1998). A Theorised History of Skateboarding with particular reference to the ideas of Henri Lefebvre [Doctor of Philosophy, The Bartlett, University College London].

Borden, I. (2019a). Skateboarding and the City: A Complete History. Bloomsbury Visual Arts.

Borden, I. (2019b). Skatepark Worlds: Constructing Communities and Building Lives. In V. Kilberth & J. Schwier (Eds.), Skateboarding Between Subculture and the Olympics: A Youth Culture under Pressure from Commercialization and Sportification (pp. 79–96). Transcript Verlag. https://doi.org/10.14361/9783839447659

Brazee, C. D. (2012). East Village/Lower East Side Historic District Designation Report [Landmark Designation Report]. NYC Landmarks Preservation Commission. https://s-media.nyc.gov/agencies/lpc/lp/2491.pdf

Campo, D. (2013). The Accidental Playground: Brooklyn Waterfront Narratives of the Undesigned and Unplanned. Fordham University Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt13x0ct9

Caramanica, J. (2011, March 24). Two Riffs on Street Wear Gone Fusion. The New York Times, 4.

Carayol, S. (2009, April). 15 Things You Didn’t Know About... Early NYC Skateboarding. Skateboarder, 18(8), 120.

Chiaverina, J. (2017, November 3). No Uncool Jokers Here: Barbara Kruger Debuts Installation at Manhattan Skate Park [Art Blog]. ARTnews. https://www.artnews.com/art-news/market/no-uncool-jokers-here-barbara-kruger-debuts-installation-at-les-skate-park-9261/

Chiu, C. (2009). Contestation and Conformity: Street and Park Skateboarding in New York City Public Space. Space and Culture, 12(1), 25–42. https://doi.org/10.1177/1206331208325598

City of New York. (1981). Upper East Side Historic District Designation Report (Historic District Designation Report Volume 1). Landmarks Preservation Commission. https://s-media.nyc.gov/agencies/lpc/lp/1051.pdf

Coakley, J. (2015). Sports in Society: Issues and Controversies (11th Edition). McGraw-Hill Education.

Connor, J. (2015, July 28). Here Are the Locations From ‘Kids,’ Twenty Years Later [Alternative News Website]. The Village Voice Film Archives. https://www.villagevoice.com/here-are-the-locations-from-kids-twenty-years-later/

Craig, L. (2014). Skateboarding. Greenhaven Publishing LLC.

Cushing, D. F., & Pennings, M. (2017). Potential affordances of public art in public parks: Central Park and the High Line. Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers: Vol. 170, 245–257. https://doi.org/10.1680/jurdp.16.00042

Eisenhour, M. (2023). 1000 Skateboards. Universe Publishing.

Fitzpatrick, J. & Skateistan. (2012). Skateistan: The Tale of Skateboarding in Afghanistan. Skateistan.

Francis, J. (2023). How to Train Your Skateboard. Skittledog.

Friends from New York. (2023). Eli Morgan Gesner [Lifestyle Blog]. Friends from New York. https://www.friendsfromnewyork.com/nystory/eli

Gladman, R. D. (2002, February). Ryan McGinness: Art + Entertainment. Strength Skateboard Culture, 95–102.

Graphéine. (2022, January 19). Barbara Kruger/Supreme: Who’s hijacking whom? [Design Agency Website]. Graphéine | History of Graphic Design. https://www.grapheine.com/en/history-of-graphic-design/barbara-kruger-supreme-who-is-hijacking-whom

Habjanovic, S. (2017, July 14). The Skateroom: Skateboarding and Art for Empowerment [Culture Information Website]. Fluoro. http://www.fluorodigital.com/2017/07/the-skateroom/

Hamm, K. D. (2004). Scarred for life: Eleven stories about skateboarders. Chronicle Books.

Hayes, B. (2017). Insomniac City: New York, Oliver, and Me. Bloomsbury USA.

Hill, J. (Director). (2019, November 19). The Unspoken Skateboard Rules of NYC. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_8Ct2E9Uvto

hooks, b. (2005). bell hooks: Cultural Criticism & Transformation [Interview Transcript]. Media Education Foundation.

Hoye, J. (Ed.). (2003). Boards: The Art + Design of the Skateboard. Universe Publishing.

Hu, W. (2023, January 29). The Mecca of New York Skateboarding, Back From the Dead? The New York Times, 30.

Ihaza, J. (2018, April 8). Renegades Once, Now the Mainstream. The New York Times, 1–10.

Jenkem Staff. (2022, August 8). Enjoy This Trove of Early 2000’s NYC Raw Footage [Online Skateboarding Magazine]. Jenkem Magazine. https://www.jenkemmag.com/home/2011/11/26/nyc-skate-history-with-steve-rodriguez/

Lang, B. (2021, June 12). 26 Years After ‘Kids’ Shocked the World, a New Documentary Examines the Lives It Shattered [Entertainment News Website]. Variety. https://variety.com/2021/film/news/kids-new-documentary-larry-clark-harmony-korine-1234995023/

Lee, J. (2011, November 26). NYC Skate History with Steve Rodriguez [Online Skateboarding Magazine]. Jenkem Magazine. https://www.jenkemmag.com/home/2011/11/26/nyc-skate-history-with-steve-rodriguez/

Lepercq, E. (2021, April 7). Objet: How Skateboard Decks Became Art Collectibles [Art Blog]. ARTnews | Product Recommendations. https://www.artnews.com/art-news/product-recommendations/skateboard-decks-art-collecting-holzer-1234589035/

Louison, C. (2023a, January 29). Why Skaters Love and Resist Skateboard Parks. The New York Times, 4.

Louison, C. (2023b, June 2). The History of New York City Skateboarding [Energy Drink Website]. Red Bull. https://www.redbull.com/us-en/history-of-new-york-city-skateboarding

Macdonald, N. (2020, August 23). Carl Shipman Interview [Retail Website]. Slam City Skates London. https://blog.slamcity.com/carl-shipman-interview/

Martin, D. (2009, August 12). Andy Kessler, Skateboard Hero, Dies at 48. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2009/08/13/nyregion/13kessler.html

McDuie-Ra, D. (2021). Skateboard Video: Archiving the City from Below. Springer Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-16-5699-6

Mullen, R., & Mortimer, S. (2004). The Mutt: How to Skateboard and Not Kill Yourself. Harper.

New York City Department of Parks & Recreation. (2015). Coleman Playground [Government Website]. NYC Parks. https://www.nycgovparks.org/parks/coleman-playground/history

Nieratko, C. (2010, December). Red Bull Manny Mania | NYC August 21-22, 2010. Skateboarder, 20(4), 30–31.

Palumbo, J. (2018, November 8). Revisiting Diane Arbus’s Final and Most Controversial Series [Art Blog]. Artsy. https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-revisiting-diane-arbuss-final-controversial-series

Panza, B. (2022, March 6). New Doc Reveals UWS as Skateboarding Sanctuary of ’80s and ’90s [Community Blog]. I Love the Upper West Side.Com. https://ilovetheupperwestside.com/new-doc-reveals-uws-as-skateboarding-sanctuary-of-80s-and-90s/

Porter, J. (2005, June 24). Under a Bridge, And on Top of the World; A Skateboarder Gets a Voice In the Redesign of a Beloved Spot. The New York Times, 1.

Prentiss, A. M., Skelton, R. R., Eldredge, N., & Quinn, C. (2011). Get Rad! The Evolution of the Skateboard Deck. Evolution: Education and Outreach, 4, 379–389. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12052-011-0347-0

Raffel, A. L. (2017). Merchandise, Promotion, and Accessibility: Keith Haring’s Pop Shop [Doctor of Philosophy, The Graduate Center, City University of New York]. https://academicworks.cuny.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2930&context=gc_etds

Rajendran, M. (2012). The Development of Streetwear and the Role Of New York City, London, and Supreme NY [Master of Arts, Ryerson University]. https://rshare.library.torontomu.ca/articles/thesis/The_Development_of_Streetwear_and_the_Role_Of_New_York_City_London_and_Supreme_NY/14658078

Rathbone, K., & Snyder, G. (2018, May 14). Gregory Snyder, “Skateboarding LA: Inside Professional Street Skateboarding” (NYU Press, 2017).

Riggins, E. (1981, April). Mail Drop [Letters to Thrasher Skateboard Magazine]. Thrasher Skateboard Magazine, 1(4), 7.

Roll Skateboards (Director). (2018, January 22). Skateboard Stories Episode 1—The Brooklyn Banks. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-CDh42OuLcU

Smith, C. (1965, Spring). Skateboarding around the World. The Quarterly Skateboarder, 1(2), 38–41.

Smith, R., Kennedy, R., & Loos, T. (2016, November 25). Holiday Gift Guide: An Invitation to Live Colorfully Through Art: A Surreal Umbrella, Lush Books, Bold Scarves. The New York Times, 28–29.

Smithsonian. (2017). Skateboards and Invention [Museum Website]. Smithsonian. https://www.si.edu/spotlight/skateboards

Smithsonian Institution. (2016, July 1). The Future of Innoskate [Museum Website]. Lemelson Center for the Study of Invention and Innovation | Innoskate. https://invention.si.edu/node/13224/p/474-future-innoskate

Snyder, G. J. (2017). Skateboarding LA: Inside Professional Street Skateboarding. New York University Press. https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt1pwt99c

Spiotta, D. (2008, February). Ryan McGinley (Photographer). The Believer, 6(2), 45–56.

Stern, E. (1978, June 5). Best Bets: Recommendations of events, places, and phenomena of particular interest this week. New York Magazine, 11(23), 83.

Supreme. (2023). Supreme | Stores [Retail Website]. Supreme. https://supreme.com/stores/

The Museum of Modern Art. (2016). Ryan McGinness [Museum Website]. MoMA | Artists. https://www.moma.org/artists/25412

The New York Times. (1978, December 12). Age of the Uphill Skateboard. The New York Times, 15.

Turner, T. (2019). The Sports Shoe: A History from Field to Fashion. Bloomsbury Visual Arts.

Veronis, J. (2021). Park History | Montauk Skatepark [Company Website]. Montauk Skatepark.Com. https://www.montaukskatepark.com/park-history

Wees, N. (2022). The Arts of the Street: Sense Perception, Creativity and Resistance in Everyday Urban Life [Doctor of Philosophy, The University of Western Ontario]. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=11239&context=etd

Willing, I., & Pappalardo, A. (2023). Skateboarding, Power and Change. Springer Nature Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-99-1234-6

Witten, A. (2016, August 15). Remembering Andy Kessler [Blog Post Comment]. NYSkateboarding.Com: Remembering Andy Kessler (2016). https://nyskateboarding.com/2016/08/10/remembering-andy-kessler-2016/

Woolf, J. (2016, October 13). RIP Dylan Rieder, the Skater Who Changed Fashion Forever [Lifestyle Blog]. GQ. https://www.gq.com/story/rip-dylan-rieder-the-skater-who-changed-fashion-forever

Yochim, E. C. (2010). Skate Life: Re-Imagining White Masculinity. DigitalCultureBooks. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv65sw5s